Spider Lady: Unlocking the Secrets of our Spider Collection

How does it make you feel to gaze deep into the eyes of a spider? Possibly you lock eyes with one like the jumping spider pictured above, over a romantic caterpillar meal just like mom used to make. Are you fascinated and seduced, or repulsed? Perhaps you feel a combination of these things. Some might speculate that there’s an evolutionary advantage to being creeped out, and that we should heed a deep, valuable impulse to steer clear of things that are dangerous. The problem with this is that spiders aren’t—generally speaking—dangerous. If anyone should feel repulsion and wariness, the spiders should feel those sensations when they regard us. Leaving aside our distasteful paucity of eyes and legs, we’re notorious spider-killers. Sometimes we kill them accidentally—by crushing them as we go about our business—but often we do it deliberately, like my creative neighbor who hunts Black Widows with a Super Soaker. Spiders, by contrast, never seek out humans to bite or eat, and only bite when cornered. When a spider is threatened by something about to push on it—be it an incautious hand picking up a piece of wood from a woodpile or a foot thrust into a shoe—that threat triggers the spider to engage a defensive response of opening and closing its fangs. So while we should move with care where spiders might be present, we can take comfort in the fact that they have no interest in picking a fight with us.

I first learned about the basic harmlessness of spiders from SBMNH Collection Associate and SBCC Professor Jennifer Maupin, Ph.D. With her friendly, perpetually smiling eyes and soft voice—in which you can detect just a whisper of her native Tennessee—Dr. Maupin is the last person you’d expect to evangelize for anything even remotely creepy. “When I tell people that I study spiders,” she told me during a recent conversation, “the response I get from the majority of people is ‘Oh my goodness, how could you do that? They’re so scary!’” While Maupin acknowledges genuine arachnophobia—“I’ve seen it in people and it’s real, people break out in a panicky sweat”—her extensive experience bringing people into contact with spiders has led her to consider that for most of us, the fear of spiders is learned.

Dr. Maupin (at right) inspects a jar in the spider collection as SBMNH Naturalist Dylan Otte looks on

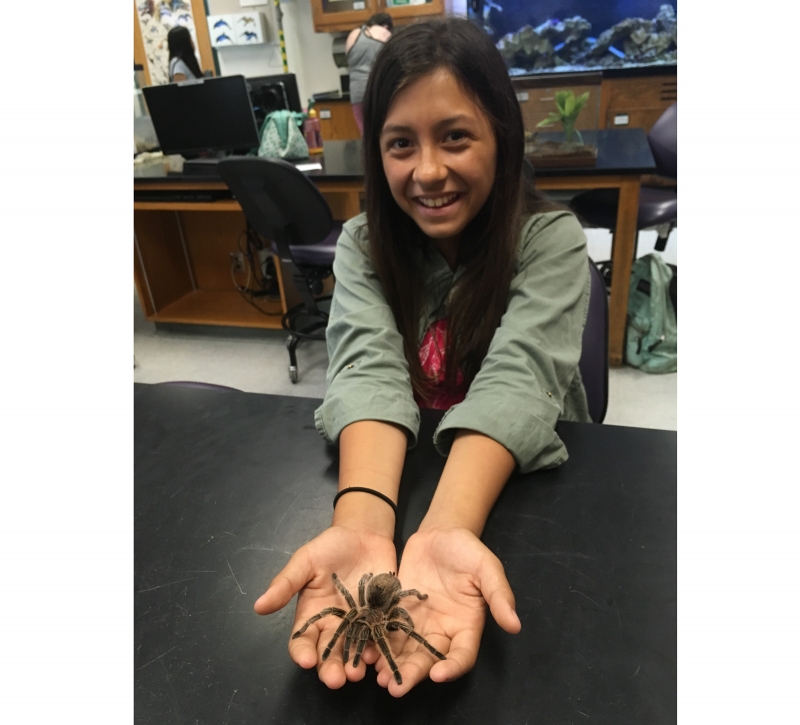

“I’ve spent a lot of time in elementary school and preschool classrooms with spiders, and I think that people think that they should be afraid of spiders when it’s not clear that they are. If you take a spider like SBCC’s Rosie the Rose-haired Tarantula to a kindergarten classroom, most of the time by the end of half an hour with these kids, probably 80% have wanted to hold her, and some of them do not want to let her go.”

Rosie the Rose-haired Tarantula with a young fan

Dylan Otte (pronounced OTT-ee)—SBMNH Backyard Naturalist and Maupin’s protégé—is a student at SBCC well beyond the age of Maupin’s kindergarten and elementary school students, but she shares their passion for contact with spiders. She remembers having an early fear of spiders: “Everybody else was scared of spiders, so I thought I should be scared of spiders.” While Otte can’t pinpoint the moment she lost that learned fear, she guesses “it might have been [after being exposed to] a jumping spider. It’s the gateway spider.”

Jumping spiders (a common name for the family Salticidae) are extraordinarily—one is even tempted to say objectively—cute. The “Tree of Wonder” in our Curiosity Lab—a tree upon which kids hang their nature questions for our staff to answer—once sported the question “What is the nicest spider?” A naturalist wrote back, “In my opinion, it’s the jumping spiders, for example Phidippus audax.” It’s not only their stout, fuzzy, teddy-bear-build that makes them “the gateway spider.” As Maupin explains, “A lot of people I talk with love the jumping spiders because of their bright coloration. Some of our more famous local jumping spiders, Phidippus johnsoni, have bright red backs, contrasting with their black bodies.”

A jumping spider (actually only about 1 cm long) from the genus Phidippus, spotted on our Mission Creek campus

In addition to showing off bright colors, these spiders put on an attractive courting display that involves drumming and waving with their appendages. “They’ll look like marching band conductors in the way they’ll move…They’re really fun to watch.” Of course, the show’s not intended for humans, but for female jumping spiders, who are uniquely equipped to appreciate the spectacle because they see better than most of their kind. “Most spiders have poor vision and rely on vibrations and chemical signals from their environment,” Maupin explains, “but jumping spiders have fairly decent vision.”

Jumping spiders constitute just one family of the 117 in the order Araneae. (The term “arachnid”—though popularly used to refer to spiders—refers to the class Arachnida, which encompasses a larger group of animals, including scorpions and other non-spiders). As much as we might prefer our cuddly gateway spiders to Black Widows and Brown Recluses (the latter aren’t found in our area, by the way), we rely on greater biodiversity among spiders for the stability of ecosystems and the comfort of our lives. Maupin quizzes Otte, “When you think about spiders, what’s a service they provide?”

“Pest control,” says Otte.

“Right. They eat insects, and that can be really important. Ecosystem services”—the ecological term for benefits humans receive from functioning ecosystems—“are very important. And there are different guilds of spiders that target different types of insects. So if you only have one type of spiders in a community, you’re not getting the full service that the spectrum of spiders would provide.” This is why “it’s important to have the wandering spiders, the funnel-web spiders, the jumping spiders, the orb-weavers” and so forth.

A Neoscona crucifera spider sheltering on a leaf in a Santa Barbara backyard

Maupin and Otte’s devotion to spiders of all sorts has been a wonderful windfall for SBMNH. Our spider collection contains over 1,500 individual specimens and spans more than six decades of collecting. As large as that sounds, it’s a drop in the bucket of the Invertebrate Zoology Department’s over 2.5 million specimens. And while our spiders are stewarded by Schlinger Foundation Chair and Curator of Entomology Matthew Gimmel, Ph.D., Dr. Gimmel is a beetle specialist pursuing his own research, properly confined to what goes on six legs. (Fair enough: beetles famously account for the lion’s share of animal diversity…suggesting that idiom is in need of revision).

The striking Peucetia viridans, also known as the Green Lynx Spider. Photo by Adam Green

So—until recently—our spiders did what many spiders do. They sat in a corner and waited…not for passing prey, but to be identified and made accessible. While each spider specimen was accompanied by critical information concerning when and where it was collected, the vast majority were only identified at a broad taxonomic level (i.e. their family was known, but not their genus or species). They had also never been catalogued, and therefore could not be digitally searched, greatly limiting the potential for their data to be put to use. In 2016, they were a collection—mostly local in scope—in need of an expert.

Dr. Maupin was an expert in need of a local collection. People—not just students, but anyone who happened to hear that she’s the local “spider lady”—were constantly asking her questions about spiders, and although her general knowledge of our region’s natural history was extensive enough for her to teach an excellent course in the subject at SBCC, Maupin felt it wasn’t deep enough when it came to spiders. She was more familiar with spider species in the areas where she’d conducted fieldwork (including the American Southwest and Northeast). Showing that healthy aversion to speculation typical of scientists, she recalls, “I didn’t have the data to really back up any statements about what spiders we have in Santa Barbara, and where they are, and how abundant they are.” To answer all the questions coming her way, she needed a data source. So in fall 2016, she took a sabbatical year to deepen her understanding, and—with Otte’s assistance—undertook the project of cataloging our spider collection. Our spiders’ patience had finally paid off.

As she came to grips with the collection, Maupin entered the existing specimen data into a spreadsheet. This was a lot messier than it sounds. It wasn’t a matter of shuffling through paperwork, but of manipulating many delicate objects, because this is a “wet” collection, in which specimens are preserved in alcohol. Tiny collection slips are nestled beside fragile specimens in wee little vials, sometimes grouped together in related bundles inside a larger, sturdier jar. This is uses space efficiently and reduces the risk of an individual vial breaking or drying out (as the alcohol evaporates if the seal on the vial is imperfect). It also makes it easier for a researcher to find related specimens. However, it made the task of creating a comprehensive database much more difficult.

Vials containing specimens from the family Araneidae (orb-weavers) grouped together in a jar

The extra effort was worthwhile, because with the collection dates and locations in a searchable database, Maupin could graph the data to visualize the strengths of the collection. Many of the spiders in the historic collection came from the Channel Islands during the 1970s and 1980s. A spike in the mid-1990s represents the single largest addition to the collection, a group of more than 250 Santa Barbara spiders collected by J.A. Calderwood. In recent years, additions by Collection Associate and Docent Sandy Russell, Maupin and Otte are catching up with Calderwood’s legacy to provide an updated snapshot of the spiders living in the Santa Barbara region.

Beyond provenance, there was still the question of identity. It may surprise you to learn that it’s often quite straightforward to identify a spider’s sex, but frustratingly difficult to identify its species. And while you might naturally expect the question of sex to be resolved by a look at the spider’s genitalia, those same spidery private parts are to key to species ID as well.

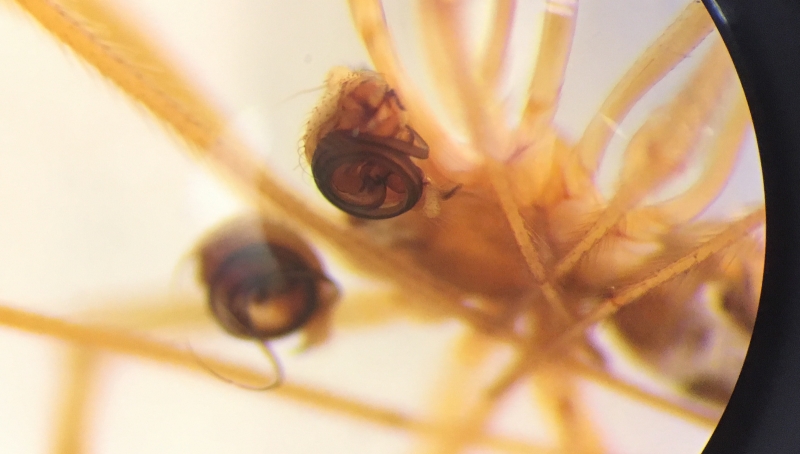

Don’t think you can spot this spider’s genitals? Think again. Adult male Xysticus californicus, photo by Adam Green

Where do you look to access this key? Female spiders have copulatory ducts sensibly tucked away on the underside of their abdomens, but male spiders go around with their implements for transferring sperm boldly sticking out of their faces. Because spiders have so many dang appendages, these go unnoticed by most humans, but Maupin will happily tell you how to spot them. “If you observe a spider closely, you can easily count their eight legs, and you’ll notice in front of those eight legs [but outside of the fangs] there’s another little pair.” These appendages are called pedipalps, and “in females…they’re straight out to the end. In males, if the male is mature, there will be an enlarged section at the tip of the pedipalp.”

Pedipalp structures enlarged under microscope. Photo by Jennifer Maupin

In many cases, the pedipalp provides the key to identifying the spider’s species, precisely because it’s a key of a less abstract kind: it fits the lock of the female’s copulatory duct precisely. Both the pedipalp and the copulatory duct have “a very unique and interesting three-dimensional structure of twists and turns” which are unique to their species. So if you need to distinguish one species from a very closely related species, you have to observe their genitalia.

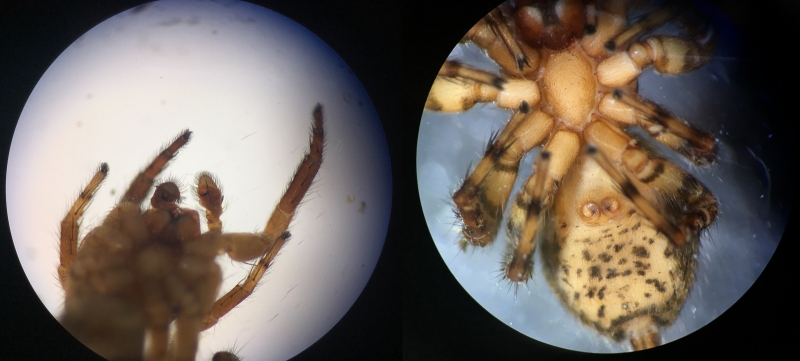

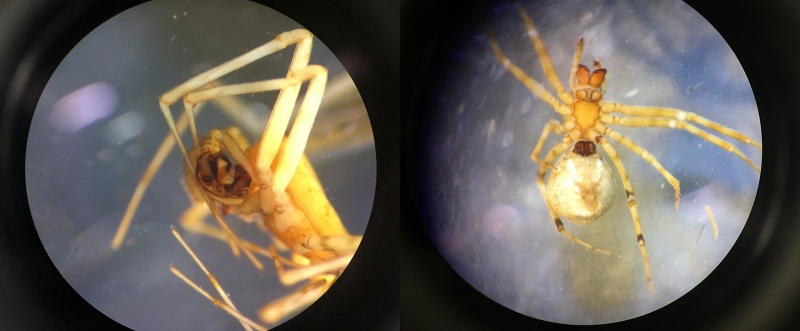

Lock and key: Mexigonus morosus (left to right) male pedipalps and female copulatory ducts. Photo by Jennifer Maupin

In this case, observing genitalia requires a microscope and serious finesse with one’s fine motor skills. Furthermore, making an identification based on these observations involves tracking down the literature that describes the species and its associated convolutions, and comparing two-dimensional drawings with an elaborate three-dimensional shape. “When spiders are alive and in their natural habitat,” Maupin explains, “they’re usually much easier to identify to family, and sometimes to genus,” because experts can look at web structures, behavioral cues, and other context to determine the species. Unfortunately, spiders in vials lack that living context, so identification in a collection like ours has to be done the hard way. So far, Maupin has been able to refine the taxonomy of hundreds of spiders in the collection.

Lock and key: Neriene digna (left to right) male pedipalps and female copulatory ducts. Photo by Jennifer Maupin

To conduct this kind of work—repeatedly, for hundreds of specimens—it’s not enough to simply not fear spiders. You have to be—as Maupin put it—“hooked on spiders.” It wasn’t always thus. Maupin recalls, “The first time I remember having a real interest in them, I was in high school. I did mission trips and community outreach with my church,” doing work at homes and construction sites where spiders were common. “I’d just stare at them…To me, one of the greatest things about spiders, specifically web-building spiders, is that you can watch their entire life right there in front of you.” (This is particularly true of female web-building spiders, who—when they reach maturity—usually settle down in one spot, get nice and big, and wait for males to come knocking.) “That’s their home, their range, their world on that web, so I’d just watch what they were doing and hopefully see them catch some prey or watch them hide.”

A spider of the genus Neoscona, at the center of its web in Goleta

As a freshman at the University of Tennessee, Maupin—who still hadn’t settled on the eight-legged kind—was interested in applying for an internship at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, DC, “because they had a living insect zoo, and I visited there in junior high school and fell in love with it. I thought, that’s where I want to work.” She told her advisor of her ambitions and was directed to talk to the “spider lady” of UT: Susan Riechert, who had connections that could help Maupin get that dream job at the Smithsonian.

Riechert had to assess Maupin as a student before writing a letter of recommendation for her, so she invited this promising student to join her for the summer doing fieldwork studying spider fear and aggression in southeastern Arizona. The phrase “spider fear and aggression” might conjure images of terrified humans squishing spiders, but the research was focused on these responses in spiders, not to them.

Agelenopsis aperta in its funnel-shaped web. Photo by Adam Green

Riechert’s classic study focused on the funnel-web spider species Agelenopsis aperta (also found locally). As Maupin explains, “Their web isn’t sticky. They have to sit at the entrance of their funnel so that they’re right at the edge of their retreat, but they have access to their web. They’ll sit there and wait for an insect to hit the sheet web, and then they run out and attack the insect.” In this context, “aggression” refers to a spider’s eagerness to emerge from that retreat, and “fear” to their propensity to stay in hiding. “To measure their aggression, we dropped crickets on the web and timed how long it took them to go out and attack the cricket. To measure their fear, we puffed air on the web, and they retreated into their funnel, and we timed the amount of time it took them to come back into the foraging position.”

Interestingly, Riechert found that a spider’s response time has a genetic basis. “We looked at two different populations,” Maupin explains. “One was a riparian population…where there were more predators, and there were also more prey available near the stream.” The spiders from this zone were understandably more fearful and less aggressive; they were adapted to a situation in which it was easy to get—and to become—a meal, so discretion was the better part of valor. The other population came from a dry hilltop where there were fewer predators and prey animals. These spiders—adapted to an environment where food and danger was scarce—were predisposed to take the initiative. They were genetically determined to be more aggressive and less fearful in their behavior.

Agelenopsis aperta. Photo by Adam Green

After one summer of fieldwork, Maupin was hooked. “I went back every summer,” she reflects. Compared with studying spiders in the field, a job at the insect zoo didn’t have the same draw anymore. In turn, Maupin got Otte hooked on fieldwork, too. Although Otte had heard of SBCC’s own “spider lady,” they met in person when Otte took the SBCC course Biology 130: Methods in Field Biology. BIOL 130 is a hands-on class that introduces students to the tools, methods, and challenges of fieldwork through a series of trips to research locations. Co-taught by Dr. Adam Green and Dr. Michelle Paddack, the course gives students the opportunity to network with researchers and visit unique habitats rarely open to the general public, including University of California Natural Reserve System sites like Santa Cruz Island Reserve, Kenneth S. Norris Rancho Marino Reserve, Landels-Hill Big Creek Reserve, and Hastings Natural History Reservation.

Maupin (at right) teaching spider sampling methods to BIOL 130 students in the field. Photo by Adam Green

Maupin often accompanies BIOL 130 classes on field trips to teach spider collecting methods used by biologists to assess the presence and abundance of spiders in an area. Because different spiders have different lifestyles—they don’t all sit around on webs in the open—it’s important to use a variety of sampling methods, rather than relying on one that will only capture certain kinds of spiders. Maupin’s tricks include sweeping tall grasses with nets, beating shrubs, sifting through leaf litter, strapping on a headlamp and spotting spiders at night by looking for light reflected from their eyes, and sucking up wandering spiders into vials with a special instrument—a kind of human-powered vacuum cleaner—affectionately known as a “pooter.” As Otte mastered these different methods, she’d already mastered the smart student’s strategy for getting noticed: “I had a plan in my head that I was just going to ask [Maupin] whatever question I could think of, just so she would know me. And it worked!”

In addition to helping Maupin with the ongoing work on our spider collection, Otte is pursuing an independent research project (which has been courteously funded by a NatureJournal Scholarship and the SBCC Foundation’s Berti Internship Fund) to learn more about the associations between spiders and plants in our region’s distinctive ecosystems. “We built a study to see which spiders live in what plant communities on what plants,” Otte explains. She collected specimens about every other month for a year, working from four plant community sites: hard chaparral (Rattlesnake Canyon), riparian zone (Rocky Nook Park), oak woodland (Douglas Family Preserve), and coastal sage scrub (More Mesa). The project will contribute to SBMNH in a very material way, as all the specimens—and detailed data about plant associations—collected in this effort will be added to our collection.

Otte sweep-netting to collect spiders in the field. Photo by Jennifer Maupin

Now Otte’s busy identifying the collected samples, which means—as described above—time at the microscope. However, she has the advantage of knowing more about the collecting context, which helps a great deal. If you bring a spider to us—as a prospective donation to our collection or as a trading specimen for Nature Exchange (a program developed by Science North)—we ask that you bring as much ecological data as possible. “Make a note about where you found the spider,” says Maupin. “What was it doing when you found it? Was it on a web? Was it a two-dimensional orb web, or a tangled cobweb? Was it running around on the ground? Was it on a plant? If you bring that kind of information along with your picture or specimen, it makes it much easier to identify.”

You can bring your spider questions—accompanied by photos, specimens, or just stories about the one that got away—to Otte in the Museum Backyard, where she works as a naturalist on Thursday through Saturday in the afternoons. If you post spider photos snapped in the Santa Barbara or Ventura areas on iNaturalist, she’ll see them, and she’s also active on Instagram as @araneusgemma (after the Cat-faced Spider often spotted in our region).

In her work as a Backyard Naturalist at the Museum, Otte helps visitors overcome their own learned fears, introducing them to our friendly creepy crawlies.

While platforms like iNaturalist are great for sharing some data, they aren’t a replacement for museum collections, which combine data with physical specimens that can be examined—as Maupin examined our collection—to extract more data. The importance of such collections goes far beyond satisfying the needs of those happy individuals who are hooked on spiders. “It’s the mission of natural history museums to document what’s in an ecosystem at various points in time,” says Maupin. “If we don’t know what’s there, we don’t know what we might stand to lose when landscapes are irrevocably changed.” Data that reveal past trends can also help us understand how future changes might play out. Although charismatic megafauna like Polar Bears capture the public imagination when it comes to envisioning the impacts of global climate change, the effects of such change on the balance of terrestrial invertebrates—so crucial to the functioning of our ecosystems and agricultural economy—could have far greater impacts on our own lives. “We know there are big impacts on some of terrestrial invertebrate species,” says Maupin. “It would be good to have documentation of what’s there. These communities and ecosystems are so complex and intricate. You never know what happens when one piece of that community is failing, what else crumbles around it.”

Mecaphesa californica, female, white form. Photo by Adam Green

The value of this information—as much as an admittedly deep-seated interest in spiders for their own sake—motivates Maupin to continue her epic task with the collection. “I want to keep working on it forever…I think hopefully they’ll let me.” This comment is representative of an attitude you’ll find widespread at the Museum and Sea Center campuses: our staff and volunteers share the desire to sit down with the good stuff and learn from it throughout life, as long as there’s space at the table. It takes a special kind of person to want to do that with 1,543 vials of spiders, but then again, it’s a special kind of place that has 1,543 vials of spiders. You might say we’re well-adapted to make just such a catch.

Otte and Dr. Maupin with a lovely jar of tarantulas (family Theraphosidae) in the Invertebrate Zoology lab

4 Comments

Post a CommentNice article and pictures, Owen! I have done a spider walk with Dr. Maupin, and I highly recommend it. And of course, jumping spiders are my favorite, too!

Wow who is that blue haired WOMAN???? She looks extremely intelligent and beautiful!

A huge THANK YOU for this article and the photos of one of the most fascinating classes of non-vertebrates in the world! At home I welcome spiders (and any other "wayward" critters) wherever they drop in; lots of them land in the bathtub or sink and cannot climb the slippery slopes; I slip a firm card under a clear plastic cup that I put over the visitor, and observe it for a moment before releasing it somewhere in the yard. Occasionally, an unseen lizard dashes out from its shelter and seizes the spider, and the circle of life continues.

This is such an interesting blog post! I learned a lot about spiders and their habits, and also enjoyed learning about some smart and dedicated staff at SBMNH. Many thanks to Owen Duncan for such a well written piece, and for the great photos that are included.