Two Years After Fire & Flood: A Community Conversation

Two years have passed since the Thomas Fire and January 9 debris flows devastated our community. For many, the losses suffered then are still very fresh. We haven’t forgotten the shock of discovering that our uniquely beautiful region is vulnerable, too. That remembrance—painful as it is—will be critical as we plan for the future, and increase our resilience in the face of wildfire and extreme weather events.

More Prepared Individuals

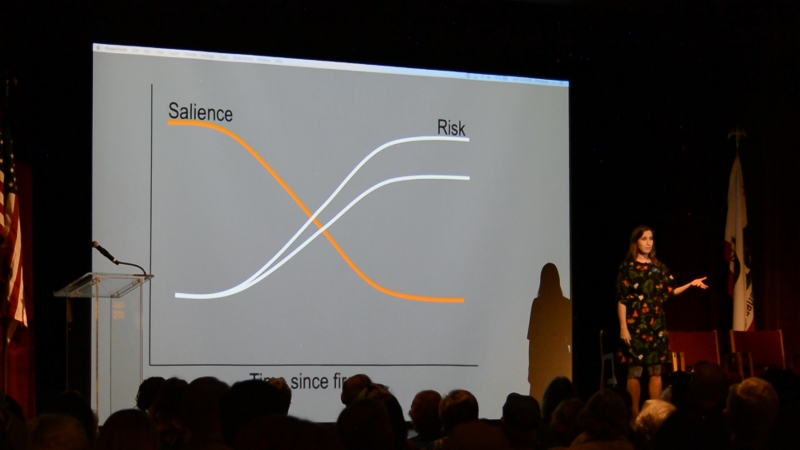

When Prof. Sarah Anderson, Ph.D., took to the stage during our recent community conversation, the connection between remembrance and resilience was central to her data. She shared the sequel to her talk two years ago, at Drought, Fire, and Flood: Climate Change and Our New Normal. (Hosted April 25, 2018 by the Granada Theatre and co-presented by the Museum, Community Environmental Council, and UCSB Bren School of Environmental Science and Management.) During that original talk, Anderson advised local residents to learn from her research as a political scientist at the Bren School, where she has studied disaster risk and planning in communities around the country. Anderson has observed how communities can best learn from disasters and take action to protect themselves. She explained how government agencies are more likely to help rebuild and make difficult planning choices when the terrible consequences of disasters are still fresh in our memories. This year, she reminded us of how salience—the freshness of a recent event—drops over time, even as risk for recurring disasters like wildfire rises again. In her words, “there’s a mismatch between our attention and what’s going on in the natural system,” as the memory of a wildfire fades while fuel for the next one accumulates.

People are most likely to prepare for future disasters when memories of recent ones are still fresh. This is precisely when risk is lowest, so it’s important to seize that moment.

To track how our community increased preparedness in the aftermath of the Thomas Fire and debris flows, Anderson’s research group surveyed Montecito residents by mail, receiving responses from over 600 households. The takeaway? “After observing this community for the last couple years, I think we actually have bent that risk curve down. We’ve taken some actions that seem to have reduced our risk in the long term.” Most residents are now more prepared for disaster: more than 40% of respondents made renovations to protect their homes from wildfire, over 70% have a survival kit and evacuation plan, about 80% are set up to receive emergency alerts, more than 60% have defensible space around their homes, and about a quarter made renovations to protect their homes from debris flow. It would be ideal if the low-hanging-fruit choices—like signing up to receive alerts—were at 100%, but Anderson still perceived that most Montecito residents were motivated to prepare for future disasters.

Prof. Anderson’s research suggests that Montecito residents have taken action to prepare for disaster and “bent that risk curve down.”

Debris Basin Lessons and Challenges

Anderson’s description of the choices made by individual residents was coupled with information about what local agencies learned from the disasters. Bren School Dean Steve Gaines, Ph.D., noted that agencies “face some really tough challenges with these extreme events . . . [they] are typically framed around coming up with . . . approaches that make sense for the normal things we’re dealing with on a day-to-day basis.” Water Resources Deputy Director Tom Fayram explained the particular challenges faced by the Santa Barbara County Public Works Department. Although Fayram reminded us that agencies had to clear even more debris after an extreme storm in January 1995 that struck a much larger portion of the region, the events of two years ago still posed a huge challenge, and raised the question: “What is the standard that [public agencies] need to prepare for?” As extreme weather events become more common with climate change, that standard is shifting.

Water Resources Deputy Director Tom Fayram answers questions during Q&A

In the aftermath of the Thomas Fire (but before the debris flows), public works expeditiously cleaned out debris basins according to their usual plan, trucking away debris. Fayram and others have questioned the wisdom of the usual procedure of treating the sediment and other natural material trapped in debris basins as garbage that needs to be removed to some distant location. In the natural course of events, this material would eventually travel down the watershed and enter the sea. The challenge facing public works is to allow passage through the watershed for some sediment, fish, and a safe amount of water, while trapping material that could damage homes and infrastructure.

Smarter debris basin design can help: “One thing we’ve learned that we’re trying to implement moving forward,” explained Fayram, “the Gobernador Debris Basin [in Carpinteria] was notched and made fish-passable, and it also allowed the natural sediments to pass through.” Obstacles remained that trapped large boulders as desired. “It was a pilot project,” and the fact that it worked during the debris flow in Carpinteria has encouraged S.B.C. Public Works to replicate the design elsewhere. “We’re now applying that to many other debris basins across the south coast, so that 1) they do a better job of stopping the large rocks, and 2) they keep the sediment in the natural system, and let it go to the ocean where it needs to go.” S.B.C. Public Works has filed grant applications with FEMA to modify Cold Spring, San Ysidro, and Romero Debris Basins in this way. Wide basins like the proposed one at Randall Road also help trap rocks by slowing water down, while allowing some sediment to flow downstream. The Randall Road Basin is also projected to move “eight [homes] out of harm’s way,” Fayram noted.

Goleta Beach sans beach (shown here during a high tide in 2017). Erosion is an ongoing problem at the park.

Beachgoers in Goleta are probably familiar with how local agencies periodically work to shore up that eroding park. Projects that add sand to a scoured beach are called beach nourishment. As Fayram explained, “At Goleta Beach we have a rock wall, because we have a deficit of sediment.” This played a role in why Goleta Beach was chosen as a place to distribute debris flow material. Fayram asked the question agencies have to ask both in the course of their regular procedure of emptying debris basins and in the course of emergency disposal: “Do we starve our beaches of this material, or do we try to reintroduce it back to the natural system where it came from? Do we haul it 70 miles away, and is that the right thing to do? . . . I would submit that [hauling material to] Buellton and Ventura County is not the answer. We need to have a location where we can sort the material out and repurpose it . . . It makes a lot of sense that that’s the beaches.”

After the event, we learned from Kim Selkoe, Ph.D. (of the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis [NCEAS], Commercial Fishermen of Santa Barbara [CFSB], and the community-supported sustainable fishery Get Hooked) that there have also been consequences for diverting boulders that once would have flowed to our beaches during major floods: “Historically, debris flows used to regularly deposit boulders into the nearshore, creating rocky reefs for kelp to grow on for a few decades before currents erode those sandstone boulders. Now boulders don’t get replenished. On our urban coastline, boulders don’t make it to the sea unless dumped there by trucks. We’ve lost our rocky habitat. Groups like Fish Reef are proposing to place new boulder reefs to stimulate kelp growth.” If we want the best of both worlds—to leverage debris ecologically while keeping it from damaging homes and infrastructure—we’ll need to be more strategic about the sorting and disposal of trapped debris.

Bacteria at the Beach

Brandon Steets of Geosyntec Consultants described in detail how the disposal at Goleta Beach played out in terms of water quality. Between mid-January and late February 2018, 40,800 cubic yards of material were deposited at the beach. “It’s not the first time that volume of material has been placed at Goleta Beach,” Steets noted, “for beach nourishment periods in the past, similar volumes have been placed there.” The material was screened for large debris and tested for toxic chemicals, to keep these off the beach. Agencies tested for fecal indicator bacteria during and after the disposal project, periodically returning to three locations in the surf zone to do so. “These are the same bacteria that are sampled [for] across California beaches all summer long,” as part of normal public health measures.

Santa Barbara County Public Health obviously closed the beach during this time, while bulldozers moved debris and the waters were turbid with newly-disposed sediment. As is typically the case during normal beach nourishment activities, levels of fecal indicator bacteria were high. “What was different this time is that the fecal indicator bacteria remained elevated for months following the disposal. This was unusual.” As a result, the surf zone of the beach remained closed for six months. In response to these health concerns, the county hired Geosyntec—which had previously worked on local beaches with UCSB researchers—to investigate.

The highlighted spike at right shows bacterial levels following disposal. The levels at left show normal elevations in bacterial levels seen in the course of the winter storms of early 2017. (Note that the increments on the y-axis of the graph increase by powers of 10.)

Steets explained an alarming graph of Enterococcus levels: “You can see what a normal winter looks like. A normal winter is about ten times the standard. What we had [during the disposal period] was a hundred times that . . . Our job was to answer why this was happening and when it would be better.” Geosyntec sampled sand and water at several sites within the most impacted zone. Their tests confirmed that the elevated bacterial levels were definitely coming from disposed material lingering at the beach.

Geosyntec sampled for human DNA markers to determine whether human waste was a contributing source to the elevated bacterial levels. This was important because bacteria from specifically human waste are understood to pose the greatest health risks to humans. The tests detected human DNA markers at levels far below EPA-imposed limits. Steets summarized: “Was human waste present at the beach? Yes. Were the levels high enough to cause illness, based on published literature? No.” He went on to emphasize the significance of the relatively low levels of human waste present in the disposed material. Although other sources (for example, animal waste and natural non-fecal sources in the environment) brought the alarmingly high levels of fecal bacteria, the level of human waste present was normal for everyday beach conditions in urban areas. “Working with UCSB researchers, we have been studying this and other beaches in Santa Barbara over the past several years, funded by the state. And we’ve found that the beaches in Santa Barbara and this beach—not unlike any other [urban] beach in California—[have] an urban background level of human waste marker, and the levels are the same order of magnitude here.” So although overall Enterococcus levels were much higher than normal following the disposal, Enterococcus from human waste was present in levels typical with everyday “bather shedding” (a charming euphemism for defecating in the sea, a privilege which should belong exclusively to marine organisms).

Goleta Beach closure due to elevated bacterial levels following disposal

“Fortunately, after our study was done, the concentrations of indicator bacteria managed to return to below the state standard.” Thanks to this, and to Geosyntec’s findings about the low level of human waste present, the county was able to reopen the beach in July. The findings also allowed the county to post warnings rather than closures as bacterial levels fluctuated in the aftermath of the original reopening. This topic was revisited during the final Q&A, when Ben Pitterle, M.S. (science and policy director for Santa Barbara Channelkeeper) commented that despite the medical understanding that bacteria from human waste is more harmful to humans, “people want to make informed decisions when they’re recreating,” and therefore sampling, posting warnings, and conservatively closing the beach is desirable when bacterial levels are spiking from any kind of waste, whether it’s from humans or from other animals.

Carpinteria Salt Marsh’s Partial Natural Recovery

The material deposited at Goleta Beach—conveyed, sorted, distributed, and monitored by humans, at a park administered with human recreation in mind—had its more natural counterpart in the story of Carpinteria Salt Marsh Reserve, part of the UC Natural Reserve System. The director of the reserve, Andrew Brooks, Ph.D., described the impact of debris flows in Carpinteria on that ecosystem.

The reserve is a biodiversity hotspot that is home to over 250 species of plants (many of which are endangered), over 200 bird species, and about 150 species of invertebrates and fish. In addition to providing habitat for these species, marshes offer important benefits to the wider area: they act as buffers protecting the land from winter storms, and—thanks in large part to plants and filter feeders—help clean the water that flows through them on its way to the ocean. However, they can only tolerate so much input. After the debris flow in Carpinteria, a volume of material equivalent to 19,500 dumpsters flowed into and across the marsh.

The marsh’s channels were clogged with “large, woody debris and sediment that washed in from the burned foothills above the city of Carpinteria, down through Franklin and Santa Monica Creeks.” Invertebrates and fish living in the channels were smothered by sediment, and “the loss of those species caused disruptions to the marsh food web,” forcing birds and other predators to go hungry or find new homes in the few remaining pockets of California marshland.

After this dramatic change, reserve administrators were faced with an important question: Was this a time to attempt a cleanup, or an opportunity to step back and learn about the marsh’s natural response? They chose the latter, in an effort to learn how resilient this kind of ecosystem might be, to observe what parts of it might recover, and how long the process would take. Two years later, the marsh has partially recovered. Whether this is good or bad news “depends on whether you’re a glass-is-half-full or a glass-is-half-empty sort of person,” said Brooks. Some channels have been restored to flowing by time and tidal action. “Not all of the channels have recovered to this degree, and many are still in a highly degraded situation,” reported Brooks. The reserve used aerial drones to quantify how channels became shallower with the introduction of debris. Surveys of birds, fishes, and marine invertebrates are ongoing to determine the long-term impacts. “My take on it is that the marsh is sort of at a tipping point. . . more impacts may push it more toward an inability to recover, beneficial changes that we may make might push it back over into that ability to recover on its own.”

Brooks concluded with four action items, listing as his goals—and calls to action for the audience—to preserve what marsh habitat exists, restore what is lost, slow the spread of invasive species, and improve the water quality of local streams. “Poor water quality is another stressor the marsh ecosystem has to face. The more additional stressors we put on an ecosystem, the less able it is to respond to these large impacts, such as debris flows.” This was a recurring motif throughout the discussion: habitats we protect with our daily actions are more likely to bounce back from big disasters, whereas the ecosystems that are already stressed by human impacts could entirely cease to function when hit by an extraordinary strain.

Restoring Our Creeks

One way of protecting habitats downstream is improving habitats upstream. South Coast Habitat Restoration (SCHR) Director Mauricio Gomez—who has over 15 years of experience working in stream restoration—introduced SCHR as a non-profit whose efforts are founded on teamwork: the organization “builds partnerships which restore degraded habitats.” They place an emphasis on helping federally-endangered Steelhead Trout (our local Distinct Population Segment is listed as endangered, its neighbors north of Santa Maria River are listed as threatened) by “removing stream migration barriers which keep fish from working their way back up the creeks.” Incidentally, one of the group’s first projects was working right here on Mission Creek, but SCHR works all over the Santa Barbara and Ventura area, working with the U.S. Forest Service in the backcountry as well as improving coastal creeks.

Gomez shared a case study of a bridge from a restoration project in Carpinteria, which was impacted by the debris flow there. He explained how SCHR coordinates with all the entities it takes to get projects like this done: landowners (private and public), foundations that offer grants, consultants who share expertise, agencies that grant permits, contractors who do the heavy lifting, and the communities that benefit. In projects like these, SCHR works to restore channels with (usually concrete) barriers to natural, fish-passable streambeds. Restored streambeds are constructed with boulders that create pools for fish, and are lined with native vegetation that stabilizes banks, shades channels, and provides habitat. In the case illustrated, the group also replaced a narrow concrete bridge with a redesigned bridge that spanned the newly-widened natural banks.

Upper Carpinteria Creek before (top) and after (bottom) SCHR’s Fish Passage Restoration Project. Photos by SCHR

Since the debris flow—as local hikers know—“our creeks look nothing like they used to look like.” The debris flow transformed the creek in the case study, scouring some areas and filling others in with sediment. It stripped vegetation, removing the “riparian trees which provided cover for a lot of the species that were in the creek channel there.” Fortunately, the debris basin upstream caught many of the boulders which would otherwise have flowed down the creek, and SCHR’s redesigned bridges held, trapping some large floating logs.

The same bridge, photographed after the debris flows. Photo by SCHR

A similar bridge just upstream (and immediately downstream from a debris basin) had trapped floating logs. Photo by SCHR

The dramatic reshaping of landscapes SCHR had so slowly and deliberately restored motivated them to convene the Fire and Flow Forum, a series of large meetings of non-profits and governmental agencies working in restoration locally. Over 150 participants assembled a master list of goals and priorities for watershed restorers in the region. (You can download the complete Fire and Flow Forum Strategic Plan at SCHR’s website.)

Gomez noted Ray Ford’s recent Noozhawk piece on newly reopened Cold Spring Canyon trails as a good illustration of how local creeks are slowly recovering. Ford writes that “the vegetation is growing back; the riparian corridors are looking much healthier; the trail community has stepped up to make the trails accessible; and people are using them in record numbers.”

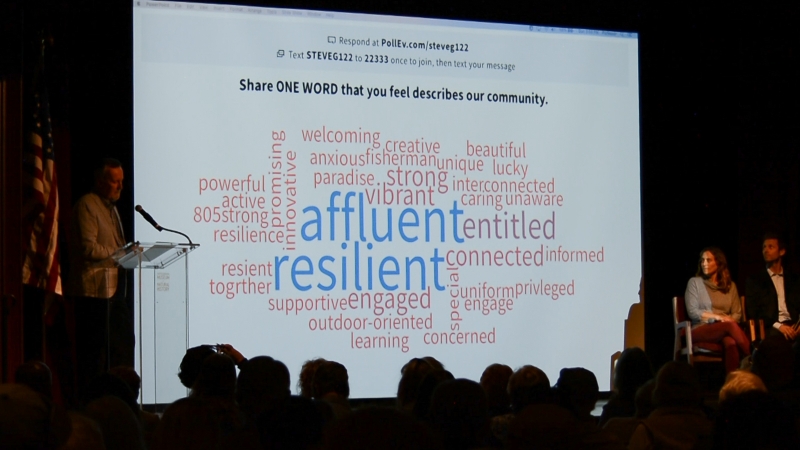

Santa Barbara in its Own Words

The perspectives of conservationists and government agencies were meshed with public feedback from the audience thanks to what we think is a technological first for our 82-year-old auditorium: the use of smartphones as polling devices so audience members could answer survey questions. Their answers appeared on the big screen in real time, slowed only by the spotty cell reception in our nook of Mission Canyon. Once folks signed in to the wifi, the flow of responses generated animated infographics, including a cloud of words audience members chose to describe our community. In case you’re wondering, “resilient” earned the most votes, seconded by “affluent,” in third place…“entitled.” The last two words served as a callback to Dr. Anderson’s remarks that the considerable wealth in our community endows us with power we should use responsibly, as we prepare ourselves and those less fortunate for future disasters.

The people have spoken! Santa Barbara is all of these things, even where contradictory.

Dr. Gaines solicited input and questions from the audience and directed queries to the experts assembled. One of the messages that emerged from audience feedback was the fact that people are eager to hear new solutions because they don’t believe the old ones will work in the face of new challenges. Audience members were asked how much they agreed with this statement: “We can effectively manage ever-increasing threats of climate change through traditional, low-tech solutions (e.g., stream bank & coastal armoring, dams, dredging, etc.).” More than 77% disagreed, about 12% were neutral, and only about 10% agreed. “We can’t become complacent,” wrote one audience member, seconded by many. Other feedback showed that the audience was aware of “the complexity of the response needed,” and felt it was time to “adapt and get out of the way of nature.”

Development and the Watershed

The latter remark—“get out of the way”—was an echo of words spoken by Pitterle. Representing Santa Barbara Channelkeeper, he framed his wariness of conventional solutions in the history of past human interventions in the watershed that have done more harm than good:

“A lot of the legacy of impact to our watersheds occurred because we historically developed in floodplains. When we did that, there was an obligation to go in and protect those homes. One of the ways we’ve done that is by altering our watersheds. We went in and channelized creeks, made them straight, to keep them from meandering, and when you do that, you accelerate the water. The water’s moving faster, and now you have more erosion issues. So we armor streambanks to protect the streambanks . . . In the worst cases, we’ve completely channelized our creeks, we’ve turned them into concrete channels, which of course destroys the ecosystem, and I would say, has an even more insidious effect in that it causes the community to not care about these places anymore, because there’s nothing there anymore, it’s just a concrete channel. There’s no more recreation, there’s no more opportunity for access, and these have long-term impacts to the community that I think we still are living with.”

The L.A. River, surely one of California’s most famous channelized waterways. Locally, we have channelized Mission Creek in the urban area, as well as San Jose Creek in Goleta.

In 2012, the City of Santa Barbara Creeks Division finished fish passage improvements to Mission Creek. In 2014, the City of Goleta completed improvements to assist fish passage in San Jose Creek (pictured). Photo by SCHR

Pitterle acknowledged that “Tom [Fayram from S.B. Public Works] has one of the hardest jobs of any of us in this room … to protect us while also navigating a very challenging regulatory environment . . . My job’s a lot easier than Tom’s in that I don’t have all the solutions and I get to point out all the problems.” However, Pitterle expressed a lack of enthusiasm for the planned construction of new debris basin at Randall Road in Montecito. “It’s important to ask, at what point do we leave these systems alone? . . . In the long term, do we think we can manage sea level rise, fires, flooding, with bulldozers, sea walls, and concrete? At some point, does the community need to face up to the fact that we’re living in places that are in the path of nature, and that we can’t control nature? . . . As a community, we need to start talking about getting out of the way.”

In Santa Barbara, it is no longer possible to pursue the course Fayram noted had once been possible with the “clean slate” of Goleta, where city planners deliberately placed open space around many creeks. In comparison, Santa Barbara is now quite developed, and development, as Brooks noted, is like “a rachet: it goes one way. We very rarely undevelop things.” He emphasized the importance of being particularly cautious about coastal development, where new buildings and infrastructure will be subjected to higher tides and more extreme storms. Community Environmental Council CEO Sigrid Wright noted how getting—or staying—out of the way of wildfire and sea level rise will mean that “we’re going to be squeezed, particularly in the Santa Barbara region . . . We’re going to be making some tough decisions about where that’s going to lead to more infill and increasing height.” City planners are already taxed with balancing the housing needs of the community with the desire to maintain the unique character that makes it a desirable place to live. Increasingly, they will have to cope with constraints imposed on development by forces of nature, with wildfire from the mountains and the rising sea.

On our many good days, we think of Santa Barbara as “nestled” between the mountains and the sea. In the coming century, it’s likely that more and more of us will feel “squeezed” by natural forces.

Dr. Selkoe alerted the audience that “the city just had a hearing about sea level rise, and [released] their new plan and analysis, and it’s pretty dire. I think that we can start to make preparations for sea level rise, and that really affects our coastal economy [and the fishing community] in a big way.”

Our Coastal Economy

Regarding the aftermath of the Thomas Fire and debris flows, Selkoe shared anecdotal evidence she gathered from her many contacts in the fishing community. While most fishermen she knew perceived that the disasters had no impact on the channel, she heard something different from

“the folks that really depend on the coastal kelp forest . . . South of Montecito to the northern Ventura border, the kelp forest declined rapidly after the debris flow. The folks that harvest the kelp on the kelp-cutter boat . . . were not able to work at those beds anymore. They take about a foot and a half off the surface of kelp—and recall that kelp is the fastest growing plant on the planet and this is not a high-impact activity—but those kelp forests were really starting to fade after the debris flow, and so they moved their operations to the north, actually off the Hollister Ranch area. And they have not gone back to that [southern] area because they feel that the kelp forests still have not recovered well. They attribute that to the sedimentation that smothered the roots, the holdfasts, of the kelp, and has not allowed the kelp to recolonize as it gets ripped out by winter storms.”

Kelp being uprooted in winter and recovering later is part of the normal cycle, but that cycle—according to the kelpers—was disrupted. “It’s all anecdotal,” Selkoe cautioned, “there’s certainly only a correlation there about the timing,” but in the absence of other data, these observations—made by people whose livelihood depends very directly on environmental health—are certainly worth noting. Selkoe put the debris flows in context: “This is a very acute event, and you layer that on top of a chronic stress, many chronic stresses our channel is experiencing, such as nitrification from sewage and other non-point-source pollution, and also warming. Our channel has warmed by two degrees in the last few years, there was a warm blob experience that happened along the entire West Coast several years ago, when we had extremely hot temperatures” that even lingered after the departure of the “blob.”

Purple Urchin barrens inhibit kelp and hurt the Red Urchin fishery species. Photo by Jeff Maassen

Like Brooks, Selkoe urged that we take action to restore and protect ecosystems on a day-to-day basis, to cushion them from dramatic events. She’d like to see the kelp beds restored, not only for the sake of the plants and animals of that ecosystem, but to assist our struggling urchin fishery. Thinking broadly about how locals and the tourists our economy relies on use the coast, she expressed a hope that local agencies could develop a good early warning system for increasingly common extreme storms, to protect boaters and people on beaches who many not be well-informed about local weather possibilities. Citing the microburst of 2017, Selkoe said, “those sorts of climate disturbances are going to become more frequent, so I think more education and awareness are key.”

Wake-Up Calls, Conversations, and Respect

Toward the end of the program, Wright called on the audience to move beyond education and awareness, and get involved in the planning process. She drew parallels between the enormous loss felt in the community following the Thomas Fire and debris flows, and the devastation of the 1969 oil spill. She described the recent events as “the turning point in the public discussion about our changing climate. I have personally worked on climate change for over 25 years, and it took these two very painful illustrations [fire and debris flow] to highlight how the changing climate is playing out on the Central Coast.” As in the aftermath of the oil spill that birthed the modern environmental movement, “people who would not have considered themselves activists were moved by the enormity of the disaster and its impact on public safety, public health, and natural systems.” She contrasted the emerging sense of ecology at the time of the oil spill with our current knowledge. “Today we have much more sophisticated tools to understand that healthy, functioning ecosystems are like healthy, functioning human bodies. . . I’ve come to think of environmental scientists like M.D.s who are sending us a very clear message: that without environmental health, we cannot thrive.”

Oil spreading from the blowout at Union Oil’s Platform A during the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill. Photo by Bob Sollen

Making that message heard in conversation is only the first step, but it’s essential to wise planning. As Wright noted—quoting past and present fire chiefs Pat McElroy and Kevin Taylor, who participated in climate threat roundtables held by CEC—one of the many functions of planning conversations is for people to meet each other and earn each other’s respect in a calm situation rather than during an unfolding emergency. “These convenings are a big step in recognizing issues in which everyone has to get out of their silos and talk to each other in advance of an incident, instead of post-incident. . . [planning conversations] help inform the decisions disaster managers make in real time. Once you get to know someone, you have respectful conversation. It becomes very difficult to dismiss their concerns.”

Eight (Among Many) Ways You Can Personally Improve Our Community’s Resilience

At the end of the Q&A, each panel member offered a specific recommendation for individuals:

1) Sign up for Aware and Prepare alerts. –Tom Fayram, Santa Barbara County Flood Control

2) Reduce your own carbon footprint. –Ben Pitterle, M.S., Santa Barbara Channelkeeper

3) Get to know your neighbors, so you can rely on each other in an emergency. Find out what different people in your neighborhood can do to help when things get serious. –Kim Selkoe, Ph.D., National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis

4) Make a habit of picking up trash and dog waste, and reduce your use of pesticides. (Doing this keeps waterways healthier so they can be more resilient in a disaster.) –Brandon Steets, P.E., Geosyntec Consultants

5) Keep telling the story of the Thomas Fire and debris flows, although it can be painful. It’s important that we don’t forget risks and lessons, and we need to share what we’ve learned with surrounding communities and newcomers to our own community. –Sarah Anderson Ph.D., UC Santa Barbara, Bren School of Environmental Science & Management

6) Be engaged at all levels. “My father used to say, ‘If you don’t vote, you can’t complain.’ ” –Andy Brooks, Ph.D., UC Natural Reserve System

7) Support groups you know are doing a great job to protect the environment and improve the community. –Mauricio Gomez, South Coast Habitat Restoration

8) Participate in planning meetings yourself. Pay attention to what’s happening at the city and county level. Local governments are often convening meetings at which public input is essential. If you can, show up and participate. This is “kind of geeky, but extremely important.” The planning processes are “only as strong as those of us who show up.” –Sigrid Wright, M.A., CEO, Community Environmental Council

Photos by @bren_life

Our deepest thanks to everyone who showed up to participate in this conversation, and to our partners in presenting this event: UCSB Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, Community Environmental Council, Santa Barbara Foundation, and Santa Barbara Channelkeeper. Generous financial and in-kind support was provided by the Museum’s Christel Bejenke Fund, Bank of America, and Strategic Samurai. Special thanks to Jo Black for providing ASL interpretation, Olivia Uribe-Mutal for providing Spanish-language translation, and UCSB Video Services for recording and livestreaming the program on YouTube.

Stay tuned for a second 2020 community conversation in fall. The topic is yet to be determined, but it should be noted that sea level rise led the audience input poll during this event.

Top photo by Ethan Turpin

1 Comment

Post a CommentThank you for this thorough recap, Owen! I wasn’t able to attend, and am grateful to get this information. What a useful event for our community.