New Curator Wants Your Help Finding Insects

An interview with new Schlinger Chair of Entomology Alex Harman, Ph.D.

Owen: You are an all-around naturalist.

Alex: I try to be. When you're outside catching insects, you run into weird-looking snakes, and you hear birds you've never heard before. It was only a matter of time before I got sucked into those other groups. Still working on plants. Plants are tough. There's a lot of plants out there.

Owen: How did entomology become your focus?

Alex: When I was about three years old, I was terrified of insects. And my grandmother, who taught entomology at the time, was not going to have a grandson who was afraid of insects. She started me off holding cute little wooly bears, those little fuzzy caterpillars, and harmless things like that. About a year later, we were cleaning out some stuff in my mom's old room at my grandma's house, and we came across her old insect collection from when she was in 4-H. If you don't take care of insect collections, little pests get in and eat everything. But there was an old, faded Pandora Sphinx Moth that was still uneaten. It became the first insect in my collection. So I started collecting at age four, and stuck with it ever since.

A young Alex Harman exploring the insect collection at the Milwaukee Public Museum in Wisconsin

Owen: Why collect insects?

Alex: Compared to a lot of vertebrates, insects are notoriously difficult to identify because they're so diverse. Among beetles and flies, there’s a lot of groups where in order to identify one to species, you're counting the number of hairs on its forehead or dissecting it to look at some of its internal organs! So we need voucher specimens; if someone's doing a study on a species, they collect a few of them and then put them in a place where they're stored in perpetuity. That way any future researchers can go back and see, did they identify this right? If the species is split or changed, which species do these belong to now?

We also collect with the assumption that in the future we’ll have even more to learn. People who were collecting specimens 100 years ago had no idea that in the future people could get DNA from some of them. There are studies now looking at pollen on bees collected 100 years ago, to study plants. There are probably lots of things you can learn from specimens that we might not even have as a concept yet.

A specimen of Omus californicus subcylindricus brimming with mysterious possibilities. Who knows what will happen to it in 100 years?

Finally, just like specimens of all the other living organisms in museums, insect collections are a great source of data for seeing how ranges change over time. It's important to establish baseline data of what insects are found where, and in what habitats, to see how their distributions shift over time in response to different climate conditions and things like that.

Owen: Range information has been a real focus of your work so far.

Alex: Yes. A lot of my contributions to entomology revolve around finding things in places they weren't recorded before. Birders, for example, spend a lot of time looking for vagrants, birds that are outside of where you'd expect them to be. Most of the time that's just a one-off individual that got blown somewhere by a storm or something like that. With insects, they're not quite as mobile as birds, so if you find something in a new spot—as long as it’s not like a dragonfly that's known for flying really long distances—there's probably a population there.

Owen: Oklahoma has a lot of grasshoppers and you know where to find them.

Alex: For my master's research, I traveled to all 77 counties of Oklahoma, surveying grasshoppers. I caught grasshoppers to see which ones were found in which counties. And I ended up with over 730 new county records—grasshopper species that hadn't been recorded in that county before. I found five species not previously found in the state. And then also while I was doing that, you know, I'm catching tiger beetles, I'm catching scarab beetles, I'm catching all the other stuff that I find as well. I ended up with a pretty good understanding of insect diversity in Oklahoma.

A lichen grasshopper, one of 131 grasshopper species known from Oklahoma. Photo by Alex Harman

Owen: How does California compare to Oklahoma, insect-wise?

Alex: Oklahoma was interesting because it's on an elevational gradient and a precipitation gradient. In the far southeastern corner of the state, you have alligators, you have cottonmouths, you have Roseate Spoonbills and all the stuff that you think of being down in a swamp along the Gulf Coast. At the far western end of the panhandle, it's 4,600 feet higher in elevation, and it's the high plains, an arid, almost desert-like grassland ecosystem. They're very different from each other, it takes about 10 hours to drive from one corner to the opposite corner.

In California, we have actual mountains, so you can go from sea level to a few thousand feet in elevation in a 20-to-30-minute drive. All that biodiversity associated with the precipitation gradient and the elevation gradient is squeezed into a much smaller area. That's part of why California—and this region in particular—is so biodiverse.

Owen: That excites you.

Alex: For sure!

Owen: What are you hoping to do out here?

Alex: Growing the insect collection is part of my overarching task. I'd like to continue spending time in the field working on research. I spent time this spring searching for lost tiger beetle species that hadn't been seen in 30 to 80 years. I’ve also been looking at the different subspecies of the Oblique-lined Tiger Beetle and I’ll be collaborating with geneticists to try and sort out their taxonomy. So far I’ve been doing fieldwork for that project along the Santa Clara River near Santa Paula, on remnant grasslands in the middle of the Central Valley, north of Carrizo Plain National Monument, and in the Cuyama Valley.

Dr. Harman has a net and he’s not afraid to use it. Photo by Emerson Harman

Owen: What is your favorite way to collect bugs in the field?

Alex: I like actively netting tiger beetles and butterflies. It's somewhat challenging, and you look ridiculous doing it, but it's fun. I’ve also gotten into using portable light traps recently, using little $11 blacklights sold as dorm room decor. They plug into a portable battery pack, and you can set those out overnight over a pan of soapy water that collects the insects. Those work remarkably well and are a lot cheaper and easier to use than the standard light trap equipment.

Owen: But you can’t spend all your time in the field.

Alex: No. I have to curate and maintain the collection, or there’s no point in collecting. On the maintenance side, I've been working to identify and curate groups of insects that hadn't received much attention here previously. The past two curators were primarily beetle-focused. Grasshoppers have been somewhat overlooked, so I’ve been identifying a lot of our unidentified or misidentified grasshopper specimens, and remounting a lot of them in a way that shows the hindwing, which can be important to identification. In terms of the strengths of the collection, we’ve also received substantial donations of moths and butterflies.

Owen: Because of our blockbuster exhibit, butterflies are a big deal here. Describe your relationship with butterflies.

Harman with a Blue Morpho in Butterflies Alive! (exhibit open through September 1 in 2025)

Alex: I've enjoyed catching butterflies my whole life. And since they’re bright and showy, you can count them without having to net every single one. That’s useful for surveys. They're really easy to do mark recapture studies on, because they're not digging underground and wiping off whatever marks you put on them like beetles are. They’re usually easier to find than grasshoppers. As far as the butterfly exhibit itself is concerned, I’ve been helping with it behind the scenes. I’ve helped with advising on various outreach materials. I spend Thursday afternoons helping to glue each of the tiny chrysalids onto rods for the emergence chamber. It's honestly a nice, relaxing way to spend an afternoon. Two of my dissertation chapters were actually focused on butterflies.

Owen: We look at butterflies as a gateway to getting people interested in other arthropods. What do you think we should be teaching people about insects and arachnids generally?

Alex: Just how important they are to the environment and the variety of roles they can play. A lot of times as an entomologist, you get two questions. You get a picture of a really blurry insect and you're asked, “What is it?” That's great. If you can identify it, that's half the battle right there. And then the second half, which is a bit more nuanced, people ask, “Is it good or bad?”

A lot of the general public, they see “bad” bugs like mosquitoes, ticks, and things like that. And then they see the “good” bugs, which are really just the ones that people like: honeybees, ladybugs, butterflies. But the vast majority of insects, they're just doing their little insect thing. They're not impacting humans directly by biting us or making honey we can eat, but they play important roles in the environment. So just because this beetle might not have any impact on you as a human, it might be an important food source for some sort of bird in the area. Or it could be a predator of some pest insect that otherwise would overrun some plant species, and it spirals out from there. I think conveying that insects are important not just because of their relationship to us should be the big overarching message.

Owen: Utterly. Your dissertation for Oklahoma State University had a wider view of ecological relationships in it, too, didn’t it?

Alex: Yes, it was about ecology and conservation. It began with grasshoppers and fire in Oklahoma grasslands, and ended up extending to all kinds of species in a really special kind of grassland habitat.

This unassuming tallgrass prairie in Oklahoma conceals dozens of species of grasshoppers, rare butterflies, and unique beetles. Photo by Alex Harman

I started with a study looking at how grasshoppers were impacted by prescribed burning. In the Great Plains, in order to keep the grassland as grassland, it generally needs to be burned every three to four years. If you’re going to do that much burning you better understand the system. And so there's been a lot of studies over the years that have looked at how is this or that species of birds, butterflies, etc. is impacted by fire. The studies looking at grasshoppers had inconclusive results because they lumped in grasshoppers in overlapping ways based on different traits. A short-winged species is going to have higher mortality than a long-winged species that can escape a fire. But if a short-winged species feeds on a plant that comes up in higher numbers after a burn, it’s complicated. So I looked at grasshoppers at the species level, rather than lumped by traits, to see how each species was impacted by prescribed burns.

Next I got an opportunity to pick up a project for the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife and Conservation on the Ozark Glades. These glades are little isolated grasslands in the Ozark Mountains in Arkansas and Missouri and eastern Oklahoma. They have a lot of grassland species that are not found anywhere else in that region: things like roadrunners and collared lizards. The glades in Missouri and Arkansas have been really well studied, but not those in Oklahoma. The overall goal of the project was just to see what's out there.

Where would you start looking for wildlife in this glade? Photo by Alex Harman

Me and a master's student did camera trapping for mammals. I did bird point counts. We did herp [reptile and amphibian] surveys, setting out cover boards for lizards and snakes and salamanders to hide underneath. And then we did a variety of insect surveys as well. I did visual butterfly surveys, sweep netting for grasshoppers, and visual surveys for tiger beetles. We set up traps for carrion beetles. Finally, we looked at what factors impacted what species were found where. Is the size of the glade important? Is the amount of tree cover within the glade important? Things like that.

While I was doing all these surveys I found a large population of Diana Fritillary, a big, spectacular butterfly species that has declined throughout much of its range. So I did a mark recapture study on that population, where you put a number on their hindwing, let them go, come back the next day, catch all the ones you see, and record which ones were already marked. By doing that for a few days in a row, and plugging it into an equation, you can estimate how many there are in that population. We also found that female Diana Fritillaries are active around dusk, which is interesting. No one had published that before, and the females are notoriously hard to find throughout the summer.

A Diana Fritillary marked for the study. Photo by Alex Harman

Lastly, because we had all this butterfly count data, I compared it to iNaturalist data from the same counties. This showed which groups tended to be over- or underrepresented on iNaturalist, just looking at some of the biases there.

Owen: Your work on iNaturalist is extremely cool. A lot of people start or end their day with a little puzzle on the phone to stretch or relax their brains, and you start and end your day by reviewing tiger beetles on iNaturalist.

Alex: Yep. I have reviewed iNaturalist tiger beetle submissions pretty much daily since August 2017. The common North American species are pretty recognizable from photos, so each one only takes three or four seconds to identify. I’ve identified over 60,000 observations like this. If I’m the first one to suggest an ID, hopefully someone else will come along and confirm it, which makes it what they call “research-grade”.

Owen: Is the identification weighted in any way based on who it's coming from? Or could it just be two bozos on iNaturalist?

Alex: It can just be two bozos. So I have extra responsibility as an iNaturalist curator—a role that gets some additional editing powers. I can’t simply ID the things that need ID. I need to go through and help fix what’s been misidentified. Nowadays, when you submit a photo, iNaturalist has image identification software built in that will give you a preliminary ID, and that can mix things up if two beetles look similar.

Owen: Someone of my Sea Center colleagues recently uploaded a picture of a gigantic sea hare, and that preliminary image thing identified it as a cow.

Alex: So that's one of its weaknesses! It's really good with some things, like more abundant plants. For North American birds, it’s pretty solid because there are so many photos out there for it to learn from. With insects you start getting a little iffy. So people step in to add their identifications. And what you end up with is this ever-growing database of observation records of everything from fungi to plants to animals. And it’s worth the effort to curate. Several of my publications have been about projects that used iNaturalist submissions by community scientists as jumping-off points for more research.

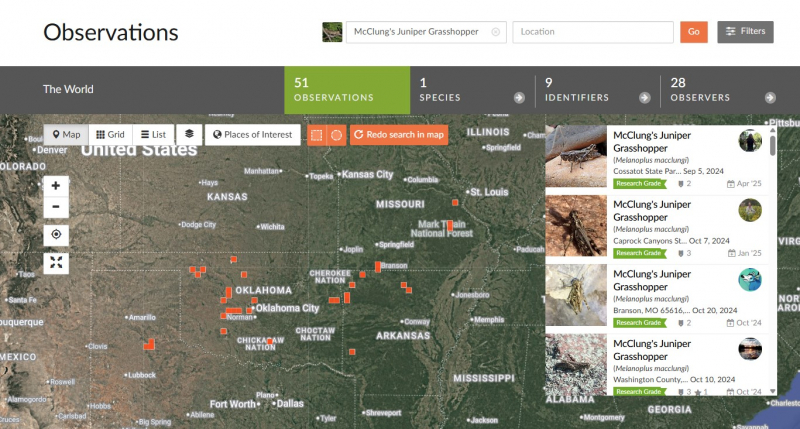

Before 2019, McClung’s Juniper Grasshopper was only known from one site in south-central Kansas. Thanks to iNaturalist submissions and surveys conducted by Harman, it is now known from many sites spanning five states!

Owen: Your recent publication followed up on some community scientists’ iNaturalist observations, to discover new and lost populations of rare tiger beetles. With many species of insects worldwide being affected by habitat loss, it’s amazing to have this tool to discover hidden populations. Is it in the nature of iNaturalist to give you good news?

Alex: Except for invasive species. Say you have an Emerald Ash Borer that turned up some new place, that's not great. I actually identified the first one submitted from the Dallas/Fort Worth area. So that wasn't good, but usually it's good when you find a species somewhere it wasn't recorded before.

The biggest strength of iNaturalist is the amount of observations that are taking place. As an insect collector, I can go out and I can catch all the insects I see, or at least the ones I'm interested in, but I can only cover so much area at one point in time. I only have so much funding for travel, I can't travel to every single sand dune in the United States and see what tiger beetles are there. But if you have an army of tens of thousands of users out there taking pictures of everything…the vast majority of those observations are going to be your honeybees, your dandelions, your things that people see every single day. But you put enough people out there who love nature and go to weird places, they're inevitably going to photograph some weird stuff. You end up with photos being posted that are new range extensions, things that haven't been seen for 40, 50, 80 years—and even new species that have been described from iNaturalist observations.

Owen: I need to get off my butt and start submitting things for you to identify!

Alex: Absolutely. You will find me on there. If you submit a tiger beetle observation, you can be sure I’ll see it. If you want to see what I’m finding, you can view my observations.

Owen: With pleasure.

1 Comment

Post a CommentExcellent interview, Owen! Looking forward to seeing all that Alex does as curator of this great collection.