She's Here for the Sea Bugs

An interview with visiting Ph.D. candidate Siena McKim, who came to borrow some amphipods from the Department of Invertebrate Zoology (IZ)

Owen Duncan: What are amphipods? I feel like they’re a kind of marine crustacean, right?

Siena McKim: Yes. You already know amphipods. If you go to the beach, you have these beach hopper guys hopping around—those are big amphipods. You think they're eating you, but they're not. They're just like, “Are you dead? If you are, I'm going to eat you.” Most amphipods are in the sea.

You know this amphipod: it’s a beach hopper! Photo by Siena McKim

Owen: I think I touched a giant deep-sea one at Monterey Bay Aquarium.

Siena: Those are isopods, which are closely related. I came here to study the Museum’s amphipod specimens because I’m interested in how some amphipods make silk.

Owen: Like spiders?

Siena: Yes and no. It comes out of glands in their legs, not their abdomen!

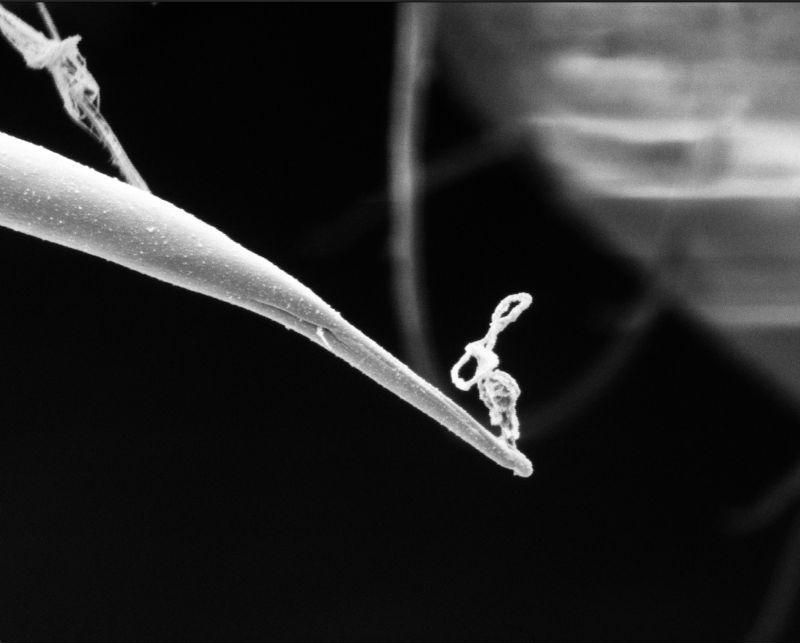

This extreme close-up made by a scanning electron microscope reveals silk exiting an amphipod’s silk glands at the tip of a leg. SEM by Siena McKim

Siena: They do a variety of things with it, depending on the species. They use silk to build tubes for shelter and to help them filter-feed. Some tubes are hard, some soft. Some tubes are sandy, some are papery. You can see the hard, papery tubes if you look closely in local tide pools.

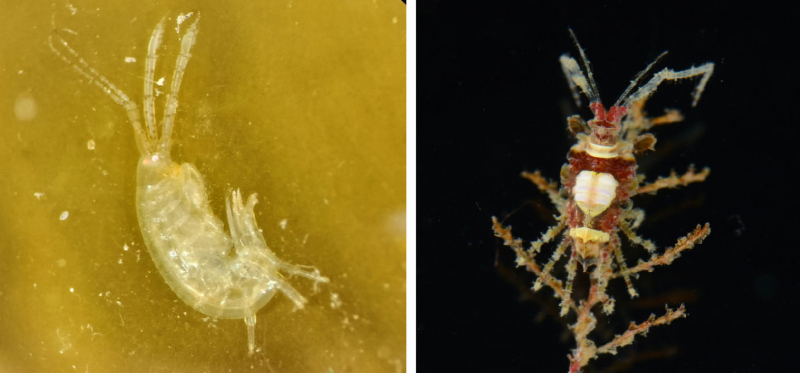

Some tube-building amphipods you might see in the wild: At left, Erichthonius basiliensis builds hard, sandy tubes found in local harbors. Right, Notopoma sp. builds a hard, papery mobile home—look for them on surfgrass in local tide pools. Photos by Siena McKim

Siena: Some of them will build these sandy poop rods to host their family—structures made of sand, silk, and poop—and they’ll raise multiple generations on there. Look at this picture (below). All these little dots on here are her babies!

Mother amphipod in the genus Dulichia with her babies atop their home, a rod constructed of sand, silk, and amphipod poop. Photo by Siena McKim

Owen: What's their conservation status?

Siena: Nobody's worried about amphipods at all. They are common around the world.

Owen: Well, that’s a nice change of pace.

Siena: It makes studying them a little easier. But the downside is people are like, “Who cares? What are they even doing?” I think they can teach us a lot about how what we at first think is a simple creature is actually very complex.

They have all these interesting behaviors that could qualify them as intelligent. They're weaving the silk in specific patterns, building complex structures, and making complex decisions. When I look at these animals, especially when they're alive, actively doing their thing, it's a great reminder that everything is a lot more complex and has a lot more going on than we think it does.

Secretive silk-users: Left, Sunamphitoe lindbergi weaves nearly invisible silk pockets on algae. Right, Podocerus cristatus—thought to have lost silk-spinning capability—seems to actually use silk to stick debris on their bodies like decorator crabs. Photos by Siena McKim

Siena: When I was a kid, I wanted to be a marine biologist to study dolphins and sharks, bigger animals we can more easily observe. But when we look at the smaller stuff, there's so much going on that we don't initially realize. Amphipods have taught me how intricate, complex, and intelligent animals can be.

Owen: Will our specimens be useful to you?

Siena: Oh yeah, I’ll totally be wanting to borrow these. They’re all super-intact, which is great. I can stain them to emphasize the silk-spinning glands.

One of the Museum’s amphipod specimens (Monocorophium acherusicum) under the microscope in front of McKim

Owen: What’s the value of looking up close at those glands?

Siena: It helps us understand both how they produce the silk, and how different species are related to each other.

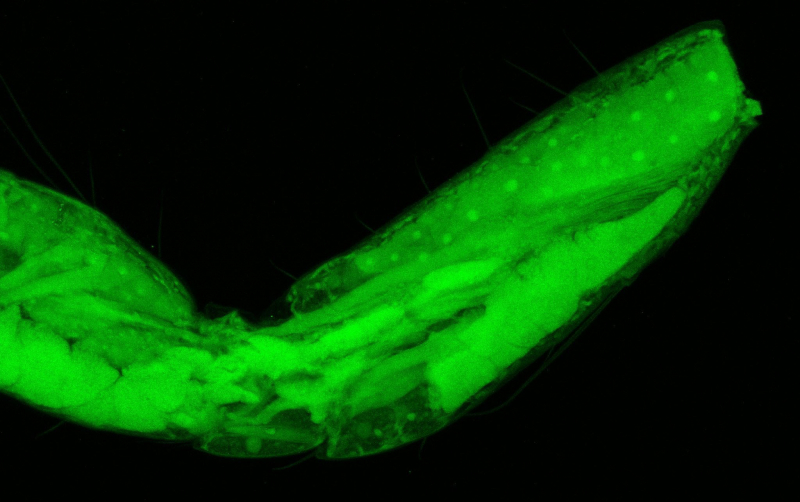

The leg of a Museum specimen stained and imaged by McKim and her undergraduate helper Siena Waldman (yes, they’re both Sienas, it’s destiny) for their research. The little green fried eggs are part of the animal‘s silk-spinning glands.

Siena: Amphipods are everywhere, they’re so diverse, and they’ve done so many cool things in their evolutionary history that are worth studying. I could go on a whole side quest about how some of them make venom.

Owen: Please do.

Siena: So the long, skinny amphipods called skeleton shrimp don't supposedly make silk anymore. They lost their third and fourth legs—the silk-making ones—but they have what seems to be venom in their second pair of legs. They have giant claws with poison “thumbs,” and the males stab each other with these. The males get really big, and the females are pretty small, and the males fight each other for access to a clump of 40 to 100 females.

This portrait of the skeleton shrimp species Caprella mutica shows the striking size difference between the sexes. Photo by Siena McKim

Siena: One of the things I’m trying to understand is whether the glands they’re using for venom have a shared ancestry with the silk-spinning glands. Maybe silk-spinning glands got co-opted for this new function of producing venom. It’s really cool that there are crustaceans that evolved venom and silk-spinning!

Owen: Evolutionary convergence—traits evolving multiple times and in different lineages—is amazing to me. As a human, I feel like I don’t have very many cool physical traits. When do I get to convergently evolve something as cool as flight, venom, or silk-spinning?

Siena: Haha, you might have to wait a couple million years. Unless you’re bacteria or a virus, evolution works a little slowly. But personally, I’m glad I’m a human so I can study all these things! A whole other thing I’d love to study are isopods—the amphipod relatives like the one you touched at Monterey—making silk. But I only have one Ph.D. to work on.

Owen: Which isopods make silk?

Siena: You are probably very familiar with pill bugs. They make silk!

Owen: Where are they putting it? You never see it.

Siena: Sometimes silk use is really cryptic. Some animals aren’t building structures, but using silk more sparingly. Pill bugs are using it only to defend themselves against predators. They'll shoot the silk out of their butt into the mouth of spiders or centipedes that are trying to eat them. That clogs their mouth with silk while the pill bug escapes. When I was doing fieldwork in Panama, I got video of isopods shooting their silk out at some forceps!

McKim's video of isopod silk

Siena: But please don’t harass them to reproduce this effect. They’re way more likely to just curl themselves in a little ball. There’s actually a verb for that: to conglobulate. That’s more energy-efficient than shooting silk.

Owen: Do amphipods conglobulate?

Siena: Not really. They can kind of crunch more into a bean shape, but they don't become perfectly globular like isopods. Generally they prefer to escape a situation rather than curling up in place.

When they’re alive, amphipods are just little bundles of joy that make me so happy. I would even call them charismatic. This morning I was leading a group of people looking at them in the tide pools at Coal Oil Point, and, people were like, “Whoa, I see them coming out of their tube! I can see them spinning silk!” It’s so cool.

Owen: Did you need a magnifying glass to see that?

Siena: Yeah. You have to make an effort to see them. But I think they’ll have their time to shine. People will discover them at some point and realize they’re cool.

Owen: You heard it here first!

Visit Siena’s website to follow her research.

Top photo: McKim looked at a selection of the Museum’s amphipods in the IZ lab, to pick some suitable for further analysis and imaging.

1 Comment

Post a CommentVery cool research and photos! Siena is awesome. Thanks for sharing, Owen.